Being over 200 years old, 26″ Kenyon saws like these are rarely found today. This is primarily because handsaws become dulled through use and the teeth must be regularly resharpened by filing. Over time, with repeated sharpenings, the saw plate gets narrower and narrower until it becomes so narrow that it is no longer rigid enough to withstand the force of sawing without buckling, at which time the saw is either discarded or the blade is cut up for other purposes. These saws pictured here must have either been stored or lost for a long time to have survived until now with such relatively full saw plates. The handle repair on one of them, even though awkwardly cobbled together, demonstrates how much their owners valued these saws.

These saws are important in this history for two main reasons. First, John Kenyon & Co is recorded as being the earliest large saw making business to work in Sheffield, England, beginning in the mid 18c and staying in business for over a century and a half. During that time Sheffield became the most prominent tool making center in the world. Second, due to a lucky occurrence of preservation, there is an 18c chest containing a complete set of tools at the Guildhall Museum in Rochester, England which includes virtually unused examples of all the kinds of joiners saws made and sold by Kenyon at the end of the 18c. The chest was made in 1797 by Benjamin Seaton to contain his father’s gift to him of a complete set of tools and was apparently put into storage shortly after being completed. The barely-used saws in it all have full plates and undamaged handles, thus showing what the saws looked like when new. The Seaton Chest has become a sort of touchstone for many hand tool woodworkers and consequently the Kenyon name is well known and honored among them today.

There are few saws known today to have survived from the 18c (Simon Barley, our most knowledgeable saw historian, suggests fewer than 150), but there appear to be many more from around 1800, just at the cusp of the 18th and 19th centuries. Using our limited information on dating, it seems these Kenyon handsaws shown here may have been made anytime from 1780 to 1810, but are most likely from the later end of that period.

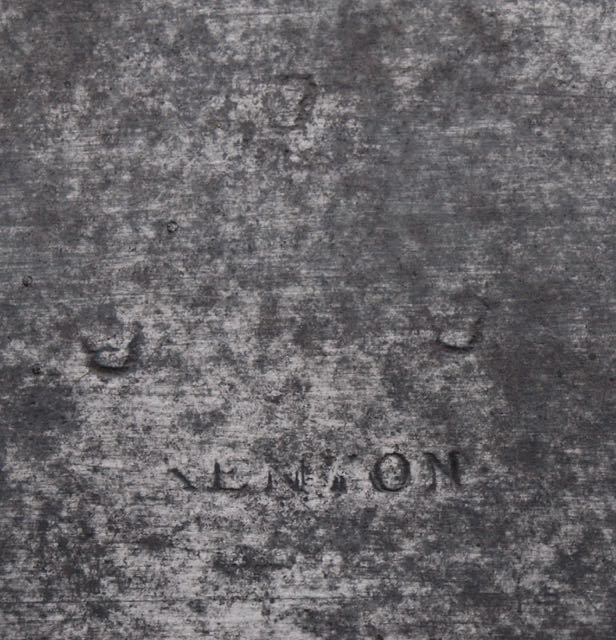

Three of the four saws shown here are die stamped on the blade with the name “Kenyon” surmounted by three crowns, while the fourth saw is die stamped “Kenyon” above“Cast. Steel”. My opinion is that the two lower stamps shown above are the earlier of the four (note the squiggly lower diagonals on the K’s in the lower two images).

The blades all display the rounded nose common to saws of this early era. It took extra work to round the blade in this fashion, so perhaps efficiency of production was the reason the round nose was lost as it gradually changed to a more rectangular shape around the turn of the century.

The handles are all of the London pattern (sometimes called the London flat) which was common on English saws through the first third or so of the 19c, after which it seemed to be used mostly on lesser quality saws. The handle pattern is very uncommon, but not unknown, on American saws. Most existing American saws were made after 1830 or so.

Three of the handles are certainly made of beech; two are plain sawn and one is quarter sawn. The fourth, repaired, handle has a dense knotted grain that I can’t identify, which may be beech as well. Three of the saw handles have three fasteners, while the fourth, unusually, has only two, as well as a very narrow nose, which seems to be almost a splinter. I believe that four fasteners began to be used on hand saws sometime early in the 19c, even as the use of only three fasteners continued on for a while, especially in cheaper grades of saws.

The size of the openings for the hand differ; two are larger and two are smaller although all only fit three fingers. I have a notion that the smaller hand holes are earlier since I’ve observed that progression in some American saws made by Welch & Griffiths, but the notion lacks any real proof.

The lambs tongues also differ; on the two handles with smaller hand holes, the lambs tongues are more relaxed, shallower and flatter, while on the other two handles the lambs tongues are more compressed, tighter and higher.

Here are some measurements of the saws, in the order of the first picture, top to bottom.

Top Saw: handle 31/32″ thick. Top edge thickness from .038-.041 Bottom edge: .042

2nd Saw: handle 15/16″ thick. Top edge thickness .044-.045 Bottom edge: .0435-.045

3rd Saw: handle 7/8″ thick. Top edge thickness: .035-.037 Bottom edge: .039-.044

Bottom saw: handle 7/8″ thick. Top edge thickness: .039-.0405 Bottom edge: .039-.041

Split nuts are 7/16″ and 1/2″ dia. The top two saws have wider & flatter bead and peak like earlier saws, while bottom two saws have thinner and higher bead & peak, like later saws.